One of the most persistent tensions in North Metro Atlanta debates—about development, schools, traffic, or taxes—is the assumption that city and county borders define lived reality. They matter legally, administratively, and politically. But in everyday life, they matter far less than we often pretend.

The discussion surrounding Johns Creek’s proposed Town Center and the Medley project has brought this tension into sharp focus. Questions about who pays, who benefits, and who bears the consequences are often framed strictly through jurisdictional lines: Johns Creek versus Forsyth, Fulton versus Gwinnett, “our” residents versus “theirs.”

The problem is that this framing no longer matches how this region actually functions.

A Region That Lives Across Lines

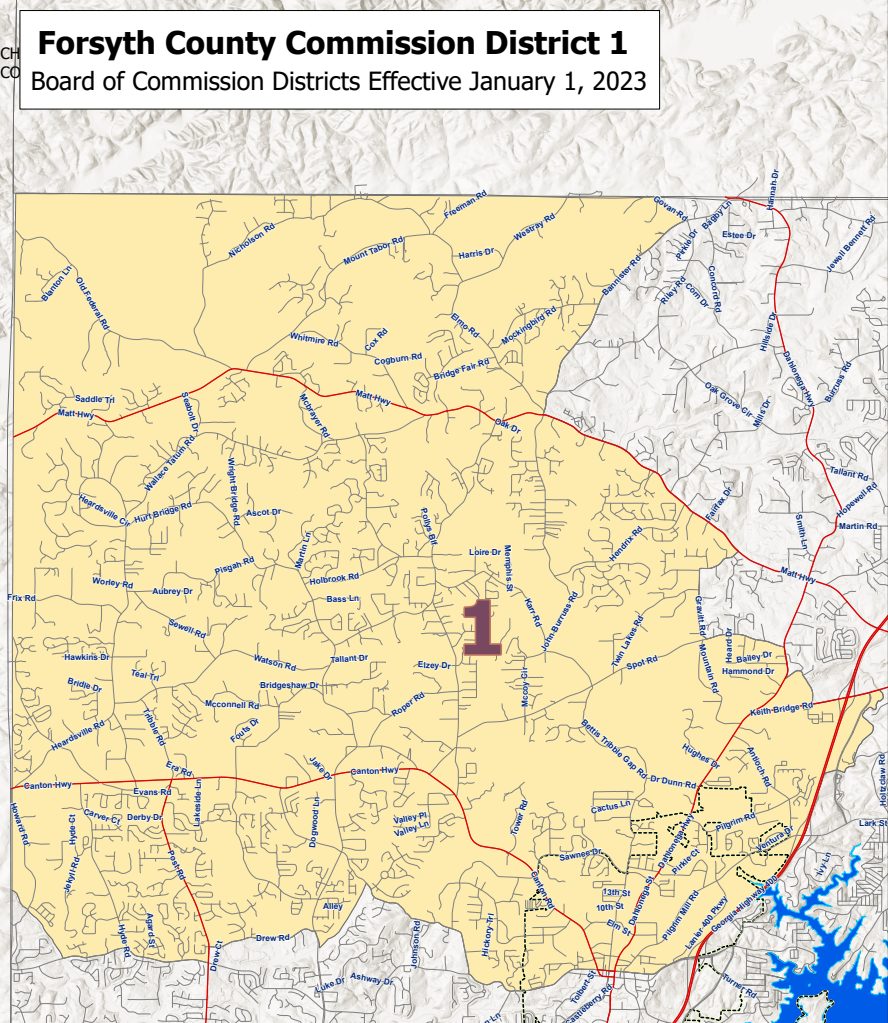

For a large share of residents, daily life already crosses borders multiple times a day. A family may live in south Forsyth, attend school-related activities in Johns Creek, shop in Duluth, and meet friends in Alpharetta—all without consciously registering that they have entered a different county or city. These boundaries are visible on maps, not in routines.

This is not accidental. North Metro Atlanta developed during a period when mobility, highways, and zoning mattered more than historic town centers or compact civic cores. Subdivisions spread outward, commercial corridors followed traffic patterns, and cities incorporated later, often to gain local control rather than to reflect distinct cultural geographies.

As a result, many borders today function less like edges and more like seams.

The Illusion of Containment

Much of the resistance to shared amenities stems from the belief that cities should function as closed systems: residents pay taxes, residents receive benefits. In theory, this makes sense. In practice, it almost never holds.

Parks, libraries, cultural venues, retail districts, and road improvements are rarely used exclusively by the taxpayers who fund them. Alpharetta’s Avalon draws heavily from Johns Creek and Forsyth. Forsyth County parks host families from across the metro area. Gwinnett’s shopping districts serve residents well beyond county limits.

This does not mean that tax equity concerns are invalid. It means that regional spillover is the norm, not the exception. The expectation that a public investment will be used only by those who paid for it is more aspirational than realistic.

What often goes unacknowledged is that spillover cuts both ways.

Who Actually Absorbs the Impact

In discussions about the Johns Creek Town Center, a common question arises: why should Johns Creek residents fund a project that people from Forsyth or Gwinnett will also enjoy?

Less frequently asked is the inverse question: who absorbs the secondary effects?

Traffic congestion, housing demand, and school enrollment pressure do not respect borders either. Because the proposed Town Center sits near the northern edge of Johns Creek, many of its immediate impacts—positive and negative—will be felt first in neighboring areas simply due to proximity. South Forsyth and nearby Gwinnett neighborhoods may experience increased traffic or housing interest long before central or southern Johns Creek does.

In other words, funding responsibility and lived impact do not always align neatly. That mismatch is not unique to this project; it is a structural feature of a region where cities and counties interlock tightly.

Schools, Housing, and the Regional Ecosystem

Few topics illustrate border-blind reality more clearly than schools. While districts are formally bounded, enrollment pressures are shaped by housing patterns that extend beyond city limits. Apartment construction in one jurisdiction can influence enrollment trends in another. A new development may shift demand rather than create it, redistributing families across attendance zones rather than overwhelming a single system.

Growth carries real costs, but those costs spread beyond any single boundary.

When families choose where to live, they rarely filter options strictly by municipal identity. They weigh commute times, housing prices, school reputations, and access to amenities across a broad area. The result is an ecosystem where changes in one node reverberate across others.

Identity in a Shared Landscape

One of the quieter anxieties behind border debates is fear of lost identity. If amenities are shared, if borders are porous, what makes a place distinct?

In North Metro Atlanta, identity has rarely been anchored in historic centers or physical cores. Instead, it has been shaped by school quality, neighborhood character, safety, and daily convenience. These are not erased by shared use. They are reinforced by how residents experience their surroundings over time.

Johns Creek does not become less itself because residents of neighboring counties dine, walk, or gather there. Nor do Forsyth or Gwinnett lose coherence because their residents participate in amenities beyond their borders. Identity in this region is layered, not contained.

Planning for Reality, Not Maps

The challenge facing local governments is not how to enforce borders more strictly, but how to plan responsibly in a region that already operates as a single, interdependent system.

This requires acknowledging uncomfortable truths: that no city builds only for itself, that benefits and burdens spread unevenly, and that regional coordination matters even when governance is fragmented. It also requires resisting the temptation to frame every project as a zero-sum exchange between jurisdictions.

The Johns Creek Town Center debate, at its best, forces a broader reckoning. It asks whether we want to plan based on how this region actually lives—or on how lines on a map suggest it should.

A Conversation Worth Reframing

Borders still matter. They determine tax rates, school governance, zoning authority, and political accountability. But they are not walls. They are administrative tools layered over a shared landscape.

Recognizing that reality does not invalidate concerns about fairness or impact. It sharpens them. It pushes the conversation beyond “us versus them” and toward questions of scale, responsibility, and long-term stewardship.

In a region as interconnected as North Metro Atlanta, pretending that cities operate in isolation is not just inaccurate—it is limiting. The more productive question is not whether borders should matter, but how communities can plan intelligently when they matter less than we think.